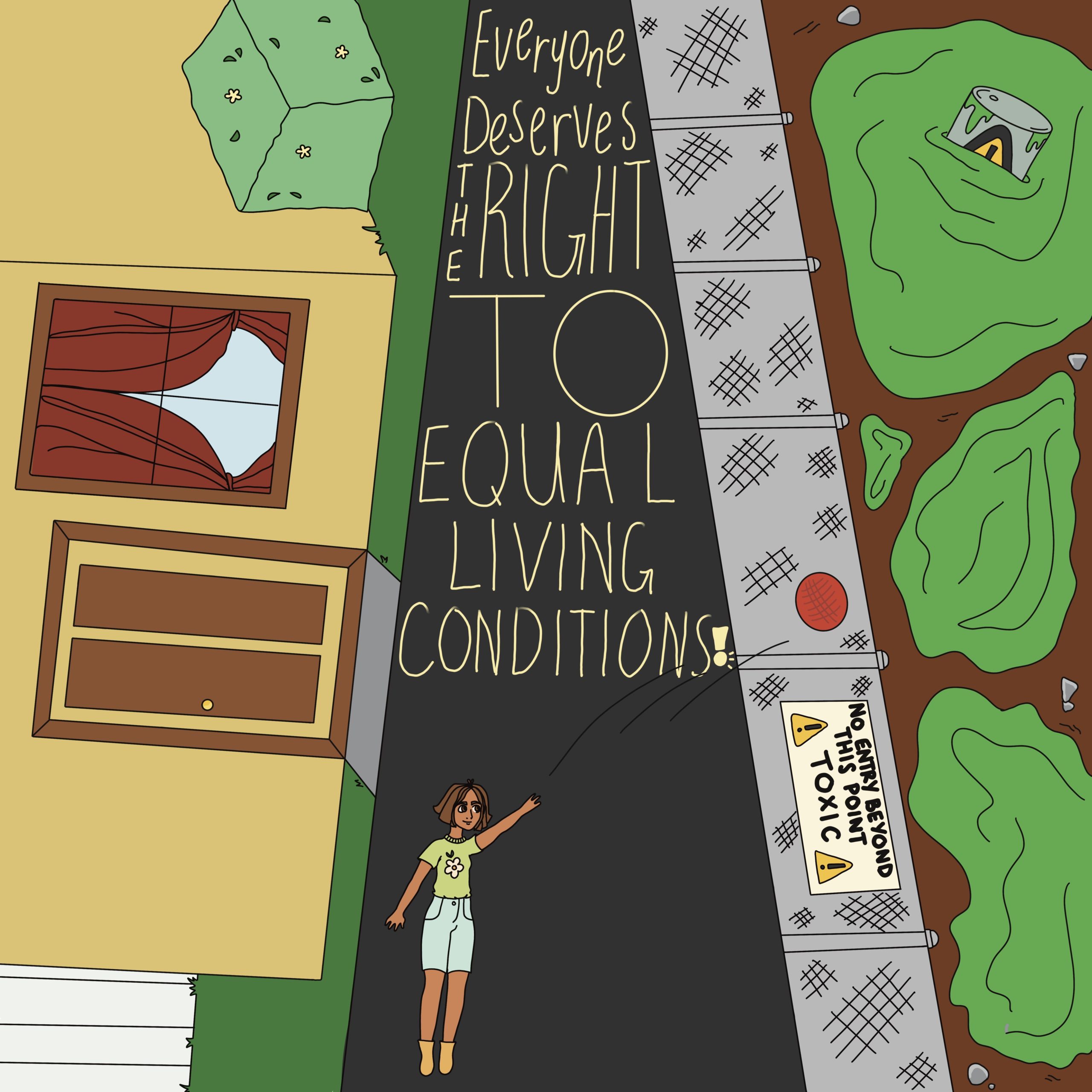

Environmental racism refers to how minority-based neighborhoods, which are populated primarily by people of color and members of low-socioeconomic backgrounds, are burdened with disproportionate numbers of hazards, which include effects of toxic waste facilities, garbage dumps, and other sources of environmental pollutants that lower the quality of life. Subsequently, as the fight with climate change worsens, minority communities will be disproportionately affected on a political, economic, social, and health level.

Many of these discrepancies are entirely due to power dynamics entrenched on an institutional level that is set up to harm minorities and low-income folk.

Millionaires make up only 3% of the public, yet they control all three branches of the federal government. While more than 50% of U.S. citizens hold working-class jobs, less than 2% of Congress has held a blue-collar job before their Congressional career. In addition, no member from the working class has gone on to become a United States President or Supreme Court Justice.

Most were millionaires before getting elected or appointed to the position. With a government inept to the working class’ woes, high housing costs, and historical discrimination, low-income and minority neighborhoods are clustered around industrial sites, truck routes, ports and other air pollution hotspots. Many are left to live near highways where trucks spew diesel, and other hazards may occur.

Environmental racism is then exacerbated by a litany of sources like redlining, racial steering, and zoning laws. While the best known examples of redlining have involved denial of financial services such as banking or insurance, other services such as healthcare or even department store shopping have been denied to residents based upon their race. Racial steering refers to the practice in which real estate brokers guide prospective home buyers away from certain neighborhoods based on their race.

Zoning is a method of urban planning in which a municipality or other tier of government divides land into areas called zones, each of which has a set of regulations for new development that differs from other zones. Zoning regulations for areas with higher value on homes are not as strict as ones for homes in lower income neighborhoods.

For instance, fracking, enabled to occur near low-income neighborhoods, is the process of injecting liquid at high pressure into subterranean rocks and boreholes, so as to force open existing fissures and extract oil or gas. If the oil or gas wells are not built well enough, they can leak and contaminate groundwater. Seeing as fracking uses huge amounts of water, it can be transported to the site at significant environmental cost. There are potentially carcinogenic chemicals that may escape during drilling and contaminate groundwater around the fracking site.

Several political and economic systems are set up to keep minorities in their low income neighborhoods, thus suffering from pollutants. The lack of affordable housing has led to high rent burdens (rents which absorb a high proportion of income), overcrowding, and substandard housing. These phenomena, in turn, have not only forced many people to become unhoused, but have put a large and growing number of people at risk of becoming unhoused.

Subsequently, there are health complications suffered from not only this displacement but the inability to leave such neighborhoods. Children from low-income and minority families are more likely to be at risk of exposure because they spend more time playing on contaminated soil than children from higher-income families; spend more time in houses that have lead paint or high dust levels; may be exposed to higher levels of contaminants in utero and in breast milk because their mothers are also disproportionately exposed; and have inadequate diets that may increase the absorption of toxic chemicals from their digestive system.

From a legislative standpoint, part of the problem is that proposed climate policies often don’t account for deeply rooted social inequities. Many people are going to be locked out of participating in a green economy if their homes are going to be destabilized. Confronting climate change requires a massive social shift.

Several health effects are spewed from environmental racism. PM 2.5 is a known carcinogen connected to premature death in people with heart or lung disease, nonfatal heart attacks, irregular heartbeat, aggravated asthma, decreased lung function, and increased respiratory symptoms, such as irritation of the airways, coughing or difficulty breathing.

Racial disparities in this exposure hold not only at a national level, but also within most states and counties. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals, which can exist in both toxic waste and air pollution, have been linked to higher rates of diabetes for Black Americans. Nitrogen dioxide (NO2), an air pollutant and greenhouse gas, affects Black Americans by a margin of 37% more than white Americans.

There are federal and local policies and policy proposals that address environmental racism and seek to reduce the harm.

The Green New Deal, a congressional bill introduced by Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Congressman Ed Markey, starts with a WWII-type mobilization to address the grave threat posed by climate change, transitioning our country to 100% clean energy by 2030.

Clean energy includes all renewable energy, such as wind, solar, thermal, and water. This policy will also redirect research funds from fossil fuels into renewable energy and conservation, will build a nationwide smart electricity grid that can pool and store power from a diversity of renewable sources, end destructive energy extraction and associated infrastructure, and will provide a jobs guarantee.

The Economic Bill of Rights, which is derived from the Green New Deal, will provide the right to single-payer healthcare, a guaranteed job at a living wage, affordable housing and free college education.

Environmental racism is a concept that has been deeply ingrained into every system present not just in this country, but across the world. While mild policy changes only address surface level impacts of the issue, it must be noted that climate justice goes hand in hand with several social issues in our society.