(This piece was originally published in Spectrum, a literary anthology comprised of winning/honorable mention submissions to the Young Writer’s Conference and was awarded the FACET award.)

I am one one-half and two one-fourths. One-half Pakistani, one-fourth Belgian and one-fourth Italian. But, (debatably) more importantly, I am many many generations. If first generation is considered first to live in the United States, I am second and third and fourth and fifth generation. This is not surprising, considering I was born into a country made for immigrants by immigrants. Also not surprising is that my one-half makes me second generation, while my two one-fourths is where it gets muddy. Yet, as our great Melting Pot will allow, my one-half will become my children’s one-fourth and their children’s one-eighth and so on until there’s no point in keeping track of the one-whatever.

The cliché is that the glass is half full or half empty because one-half is nearly a majority. No one will ever ask you if the glass is one-fourth full or one-fourth empty because it doesn’t work that way. It’s one-fourth full, three-fourths empty. There’s only one-fourth to cling on to, one-fourth to claim.

Being one one-half and two one-fourths and a hodgepodge of generations gives me an interesting vantage point. My maternal Pakistani side has always pulled me in. Lured by my mother’s Urdu-speaking family, I’ve found myself enthralled with the world they left behind. They are the first generation to live in America, and with their journey came their culture — from mouth-watering masalas to Eid prayers to three day weddings — still so fresh in their minds, in their hearts.

My paternal Belgian and Italian side has always felt starkly more American than anything else. Even though my Walloon grandmother’s voice drips with a heavy French accent as she recounts her teenage years in Nazi-occupied Belgium, her late husband’s New Jersey Italian roots brought her to suburbia. A picture-perfect 50’s housewife, a successful bread-winning husband, and three all-American boys — one a football player, one a car enthusiast, one an artist. The melting pot melts into the American mold.

Yet it would be foolish to believe my mother’s side preserved culture unscathed. They came here for college — full-scholarship, brain-drain kids. Kids who accepted America with open arms, digging into hamburgers and singing along to Fleetwood Mac. Kids who had long left Islam — a component of Pakistan so large one struggles not to generalize the country as a giant mosque. Kids who married American kids and raised American kids. So American, in fact, that our family looks like a random generator put various people in a room — we are Belgian, Italian, Korean, Black, and of course, Pakistani. Not one of the second-gens can understand the wisps of calligraphy forming right-to-left Urdu poetry. Not one of the second-gens can recite any prayers whatsoever. And so it goes.

Growing up in the diverse Central Valley. I’ve been surrounded by second-gen kids like me. Kids that tag -American on the end of their nationalities, even though we are all engulfed by the suffix. We drown in the melting pot. One-half becomes one-fourth and we pass on what is not lost in the commotion of getting through each day. Language left first, its bags packed long before we were born as our parents learned English. What leaves next? Food, as I’ve never learned to fill the house with an intoxicating masala aroma? Dress, as it’s ridiculously expensive to buy saris in the States yet equally expensive to order the hand-embroidered fabrics from Pakistan themselves? The small bit of culture I’ve managed to sink my talons into means more than anything to me. The Pakistani in Pakistani-American gives me a sense of who I am — yet one-half becomes one-fourth and one-fourth becomes one-eighth. The x-gens of all races “white-washed” and “Americanized,” melted into an unidentifiable stew in the Melting Pot. And I am scared.

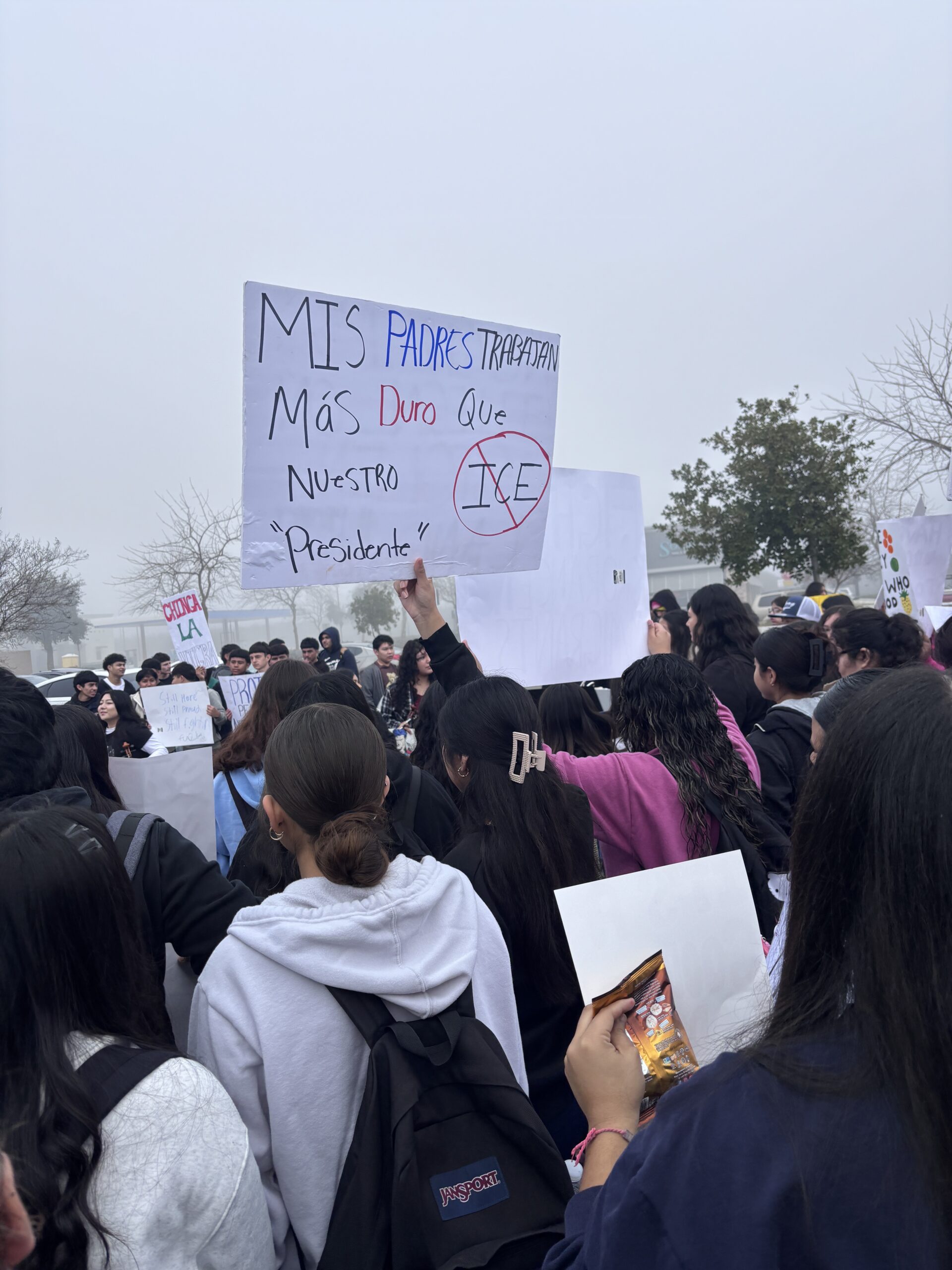

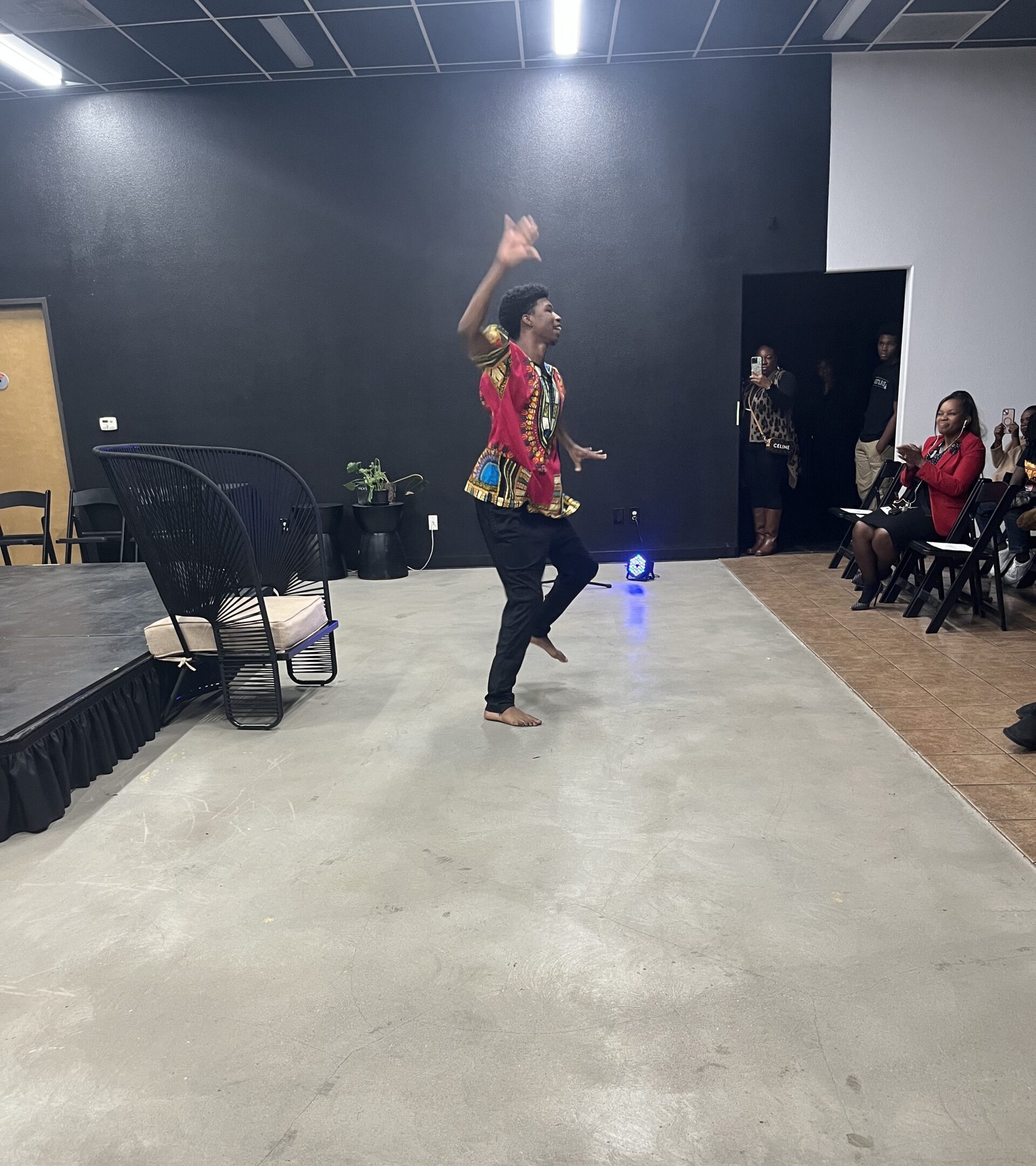

And why should we carry our immigrant ancestors’ suitcases, packed to the brim with songs and recipes and dances and literature and tradition? Because to be “Americanized” is to toss the contents of your suitcase in with the others. Because it has taken me the heartbreak of inevitable giving up aspects of my culture to realize that “Americanization” is just as much taking in others. Living in America, I know much more about Mexican and Hmong culture than my parents, and far more than my parents’ parents. I see my school celebrate Cinco de Mayo, Mardi Gras and Hmong New Year. I see my classmates translate school messages into their parents’ native tongues, a foot in each world.

These x-gen kids of all races flooded the streets on January 21st. “White-washed” and “Americanized,” they walked for the country their ancestors flocked to for a better life. They remembered an inescapable truth: we live in a country of immigrants. Although I fear my roots may melt into an unidentifiable stew, I know that one-eighth becomes one-sixteenth becomes one-thirty-second yet never zero. Never zero, as the numbers asymptote in defiance. We all have our remnants of culture pre-”Americanization” — no matter how small. We are all x-gens of all races. We are all children of immigrants.