By Claudia J. Gonzalez. This story was originally published by We’Ced Youth Media.

By Claudia J. Gonzalez. This story was originally published by We’Ced Youth Media.

CHOWCHILLA, Calif. — My heart begins to pound as I enter the gym at the Central California Women’s Facility (CCWF) on the outskirts of Chowchilla, about 20 miles south of Merced. Within moments memories of my own time behind bars flood my mind.

I can’t help but wonder at my own sense of being so at home after so many years.

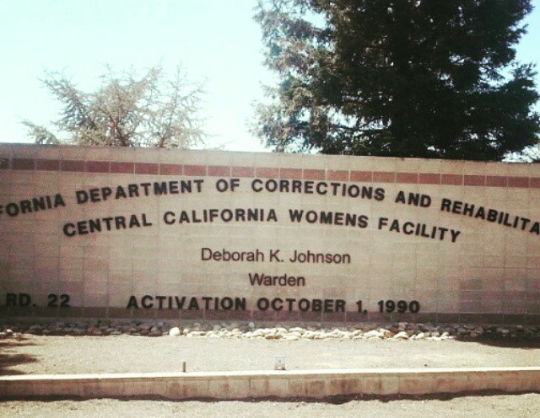

I’m here as a volunteer for a health fair co-organized by an advocacy organization and a group of CCWF prisoners. The facility is one of three female prisons in the state, and with a prisoner population of 3,123 is the largest female-only prison in the world.

Opened in 1990, CCWF has 2,004 beds, and is currently at 155 percent capacity. Twenty prisoners are currently on death row.

Niki Martinez, 38, has spent the past 20 years as at CCWF. Petite, her arms decorated with tattoos, she was sentenced as an adult for a crime she committed when she was only 17.

“I was young and I take responsibility for my crime,” said Martinez, who is serving a sentence of 45 years to life. “But [now] my goal is to help other girls avoid ending up in my situation.”

Martinez joined with fellow prisoner Elizabeth Lozano, 40, to form the Juvenile Offenders Committee (JOC) several years ago, which provides a support system for women at CCWF who were sentenced as adults when they were juveniles.

A 2010 study by the UCLA School of Law Juvenile Justice Project found that 66 percent of youth sentenced as adults develop mental illnesses. Forty-three percent were found to have three or more psychiatric disorders.

JOC currently has some 130 members. The group provides workshops on issues like substance abuse, trauma education and assistance with preparing for parole hearings.

In June, JOC partnered with the San Francisco-based organization California Coalition for Women Prisoners (CCWP) and Centerforce, which is headquartered in San Quentin and has been providing health and family services to incarcerated populations for the past 30 years, to host the 2015 Health and Wellness Fair. CCWP advocates for women, transgender people, and communities of color impacted by incarceration, and its membership encompasses both incarcerated women and activists.

Nearly 1,000 women gathered in the prison gym on the day of the event, which featured informational booths on substance abuse, transgender support, disability services and trauma. There were also a variety of activities like exercise challenges and live performances.

Martinez says events like this are crucial, not only because they identify available resources, but also because they help build morale among the prisoners and encourage them to support each other.

Sara Kershnar is a coalition member. She says the fair was “organized with the goal of giving people tools that they can use to take care of themselves and each other.” She adds that groups like CCWP are working to “build power in a place where you are humiliated, blamed, and shamed on a constant basis.”

Recent reports do in fact paint a grim picture of life inside California’s women’s prisons.

In 2013 the Center for Investigative Reporting published a report that found that between 2006 and 2010, 148 women prisoners had been sterilized without consent in California. Prisoner rights advocates called the practice a form of eugenics.

That same year a Health Care Evaluation of the Chowchilla prison by medical experts took note of the “overcrowding, insufficient health care staffing and inadequate medical bed space” available at the prison. The report’s authors attributed at least one prisoner death in 2013 to complications brought on by subpar care.

Such concerns are what drew Lamercie Saint-Hilaire to participate in the fair.

A practicing physician in San Francisco, Saint-Hilaire spent the afternoon answering medical questions and providing medical information to attendees. She says many of the questions were about health care for relatives on the outside.

“It’s amazing that even when dealing with the daily struggle of surviving prison, they still prioritized their family’s needs before their own,” recalls Saint-Hilaire, who says the trip to Chowchilla offered her an opportunity to help women in need of care, and to gain insight into health care inside the prison system.

“This experience showed me their humanity … I left the event with a great sense of humility,” she said.

I shared that same sense of humility, having spent the day listening to the stories of women whose narratives sounded so much like my own. I was at turns amazed and inspired at how many of them were eager to help others and try to give back to their communities from the inside.

As the fair was wrapping up an elderly prisoner approached. “I am so happy to see you here,” she said. “It makes me feel like somebody cares about us.”

I reflected on my own time behind bars, and how I could be where she is now had I not been given a second chance.

“We do care about you,” I replied. “Never forget that.”