By Kyle Moua

By Kyle Moua

Choua Thao wasn’t like other Hmong girls. At the age of six, she believes she was the first Hmong girl in Laos to attend school and learn English.

Her father, a regional chief, had seen other Laotian girls attend school and decided that his five children, too, should become educated. But it was unheard of for a Hmong girl to go to school, rather than learning to cultivate the fields.

Thao, now 72, recalls the disparaging comments she heard among villagers of Ban Phoukabaht, in the Xieng Khouang Province in Laos, where she grew up. Some questioned her father’s decision, calling a “stupid man,” and saying she would turn out to be lazy. “She will go be a prostitute,” she remembers hearing them say. “The lazy don’t know how to farm.”

Her father’s decision set in motion a series of events that would lead her to become a nurse during the CIA’s Secret War in Laos, and eventually flee to the United States.

Now living in San Jose, Calif., the grandmother and war veteran says it was learning English that offered her an opportunity to escape the fields and farming life traditionally expected of young Hmong women.

For eight years, Thao’s father sent her out of the house every morning at 6:00 am. She would walk for two hours to reach school in time for lessons, and walk two hours home again.

Choua Thao: Female Hmong Veteran Reflects on Secret War from The kNOw Youth Media on Vimeo. Video by Alex Taylor.

Becoming a nurse

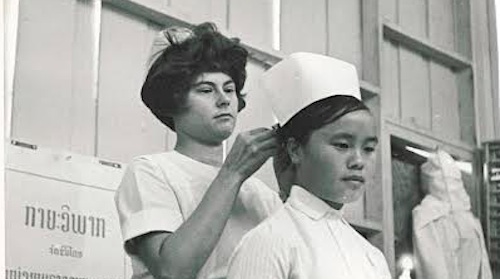

When she turned 13, she was recruited by the International Volunteer Service to join a one-year nursing program. After that she went to Thailand to train for two more years at the U.S. Udon Military Hospital.

At the age of 16, she was sent to a hospital in Xieng Khouang to “be a good example,” of Western medical practices. Trained in the “American way,” Thao infuriated her colleagues by throwing away needles and syringes after a single use. Although her fellow nurses were older and had more years of experience, Thao was a supervisor and would take on some of the doctor’s responsibilities when he was away.

In 1969, at the age of 22, with three small children, Thao was asked to oversee the busy American Sam Thong Hospital.

Thao says Edgar ‘Pop’ Buell, the American humanitarian aid worker, told her she would be the boss. “I say no… I’m too young,” she recalls. But he insisted, telling her that her language skills set her apart from the older nurses. In the end, Thao found herself working around the clock at the hospital.

Fleeing Laos

Like many Hmong who assisted the United States in the Secret War in Laos, Thao found that her close associations with the U.S. and its allies carried a high price.

The United States was not officially supposed to be in Laos through an international agreement signed in 1962. So the CIA fought communism in Laos through a secret army. Though other indigenous populations were recruited, much of the army was Hmong. The Hmong army was used to rescue downed American fighters, combat Communist forces in Laos and cause havoc on North Vietnamese forces along the Ho Chi Minh trail.

After the U.S. pulled out of Vietnam and the Lao Communist forces took over the country, the Hmong and other allies of the U.S. were targeted for death.

“It was… the Communist way,” Thao explains. “If you are working for the American, they want to capture you, take you to kill you.”

She recalls her escape from the Laotian Communists, called Pathet Lao, or Lao Nation. “They [were] late by about two hours,” she recalls. “I took off before that.”

Journey to the U.S.

Thao, her husband, Nhot Kham Sinwongsa, and their six children arrived in Winpun, Wisc. on April 15, 1976. They were sponsored by a local church, a common support network for the first wave of Hmong refugees.

Thao delayed her arrival by three months, however, because she wanted to train young women at the Napho Refugee Camp in Thailand on proper nursing techniques before she left for America. She and her family stayed at the refugee camp for nine months.

Within weeks of arriving in the U.S., Thao and her husband had found jobs. But she was determined to make a new life for her family, and set about getting an American education. “I work during the day, I go to night school for seven years,” she recalls.

With her daughter at her side, she went to the University of Minnesota for two years to get a degree in social work.

But she says her children felt neglected, and thought she was being selfish by pursuing her own education. She agreed to stop getting degrees, on the condition that her children all did well in school. ‘[If] you don’t make it, then I‘m gonna [be] very angry,” she told them.

Caring for the community

In order to help other women refugees, Thao and several other Hmong women founded the Women’s Association of Hmong and Laos (WAHL) in St. Paul, Minnesota. Initially, she says, some men in the community feared that their authority would be usurped. But Thao says she simply wanted to empower and educate women, to prepare them for their new lives.

Her reputation from the Secret War helped her gain the trust of the older Hmong men, and eventually her work on behalf of both men and women won the community over.

In 1985 Thao received an invitation from President Reagan to go to the White House. When questioned on what she wanted for her people, Thao told the president, “I’m here today, in D.C. I want to advocate for the poor in America.” Thao feels very fortunate that her father sent her to school. Her education and work allowed her to come to America in the first wave of war refugees. She in turn advocated for young Hmong women to get educated in Laos. She always pushed young people to have a dream and fight for it.

Her dream as a young girl was watching large powerful helicopters and hoped one day to be in one. As a hospital administrator during the war, she would fly to all parts of Laos to recruit young women to be nurses in the American helicopters. As she reached her dream of flying in a helicopter she helped lead the way for Hmong women in Laos and for immigrants in America years later.

Kyle Moua, 20, is from Fresno. This story was produced by The kNOw as part of a collaboration between PRI’s The World and New America Media.