By Charlie Kaijo

This story was originally published by New America America.

FRESNO, Calif. – A melancholy hum floats above the yard of Teng Her’s single story home in Fresno. The sound conjures images of the Hmong homeland in the verdant mountains of Laos, a long way from the dry expanse of the Central Valley.

But twice a week young Hmong visit Teng to learn the art of the qeej (pronounced “kheng”), a long flute-like instrument played as part of traditional Hmong funerary rites.

At 25, he is not much older than his students. But Teng’s mastery of the music has turned him into a pied piper connecting the next generation of Hmong youth to one of the culture’s most revered traditions – communicating with the souls of the dead.

As the sun sets, smoke bellows from the fire-pit in Teng’s yard. The stocky 24-year-old pulls a log from a stack. Axe in hand he stands the log upright to split for firewood. “Even if you’re strong, you need to know what you’re doing,” he tells one student, in a mixture of Hmong and English.

“He lectures like that a lot,” says high school freshman Ger Her (no relation to Teng).

As the fire builds, Ger and the other boys, ranging in age from 10 to 22-years-old, form a circle around Teng. Each await their turn to perform a single verse of a song they have practiced, one after another, returning to begin the circle again in a continuous melody that can last hours.

The qeej is made of six curved bamboo pipes, measured to precise length and attached to a mouthpiece extending upward via a single rod. Each series of notes communicates directions to the deceased for safe passage to the spirit world. Songs can last up to 9 hours, while funerals extend up to three days, with qeej players taking turns to ensure an unbroken tune for departed spirits.

Three ribs and money for gas

Teng began teaching the qeej in 2010 with a small group of around five or six students. At the time, two other teachers in Fresno were giving lessons: an elder qeej player, and Teng’s brother-in-law and former instructor, Peng-Cha.

But students were drawn to Teng’s teaching style, and so when word went around the community many left their previous teachers to learn from Teng. In 2014, Peng Cha passed away, and Teng inherited his remaining students. Today he is the only qeej instructor in Fresno, home to the second largest Hmong community after Minnesota.

He is also one of only a handful of txiv qeej (pronounced “tsee kheng”), or qeej masters in the community.

“Since all those elders passed away, and a lot of them have retired, there’s no one to teach anymore,” says Teng. “If there’s anyone out there willing to learn, I’m willing to teach just to keep on the tradition.”

For $25 a month, Teng teaches twice a week at his house and every Wednesday at a community center, 20 to 30 students at a time. On weekends, he and a small group of txiv qeej from around the area can be found playing the funeral circuit in town.

Traditionally, compensation for a txiv qeej includes three ribs from a cow slaughtered for the funeral meals, and sometimes money for gas.

“I have a lot of people who look down on me,” says Teng, who has turned away from college and pursuing a career to teach the qeej full time. “They tell me, ‘Life in America, you’ve gotta work and make money … You’ve got to charge [more]. Make it a business.’”

But Teng says trying to monetize the tradition would just as likely spell its demise.

“There’s a lot of families out there still living in apartments where it’s just two bedrooms, but there’s ten kids living in one household. They don’t have a lot of money, but they still want to learn qeej,” he says. “Some of them can’t even afford the qeej. If we make it into a business, nobody can continue it.”

A new life, and old ways

Fresno’s Hmong community dates back to 1976, when the first wave of Hmong refugees began to arrive. In 1970, the fall of Laos to the North Vietnamese set the Hmong on a migration to refugee camps in Thailand and eventually to America. Between ‘76 and ‘92, over 115,000 Hmong immigrated to the U.S., and over 30,000 resettled in Fresno.

As the community grew, so did the struggle to hold to what were largely agricultural traditions connected to the Hmong homeland, including the elaborate funeral rites.

When someone in the community passes away, a funeral committee is notified that then chooses qeej masters to perform. Ceremonies can cost up to $5,000, with well over 100 people coming for each of the three days.

“It’s just community service,” says Panh Vang, 32. A fellow txiv qeej, Vang is the fifth generation in his family to play the instrument. Between his weekly job as a FedEx franchise owner and a new dad, he spends his weekends at Hmong funerals. “I’m helping you in your time of need, and one day, I will need your help too. That’s just the way it is in Hmong culture.”

In his backyard, Teng reminds his students about a funeral happening that weekend. Most of his students have seen a dozen funerals or more. The most dedicated will follow him to a funeral a week.

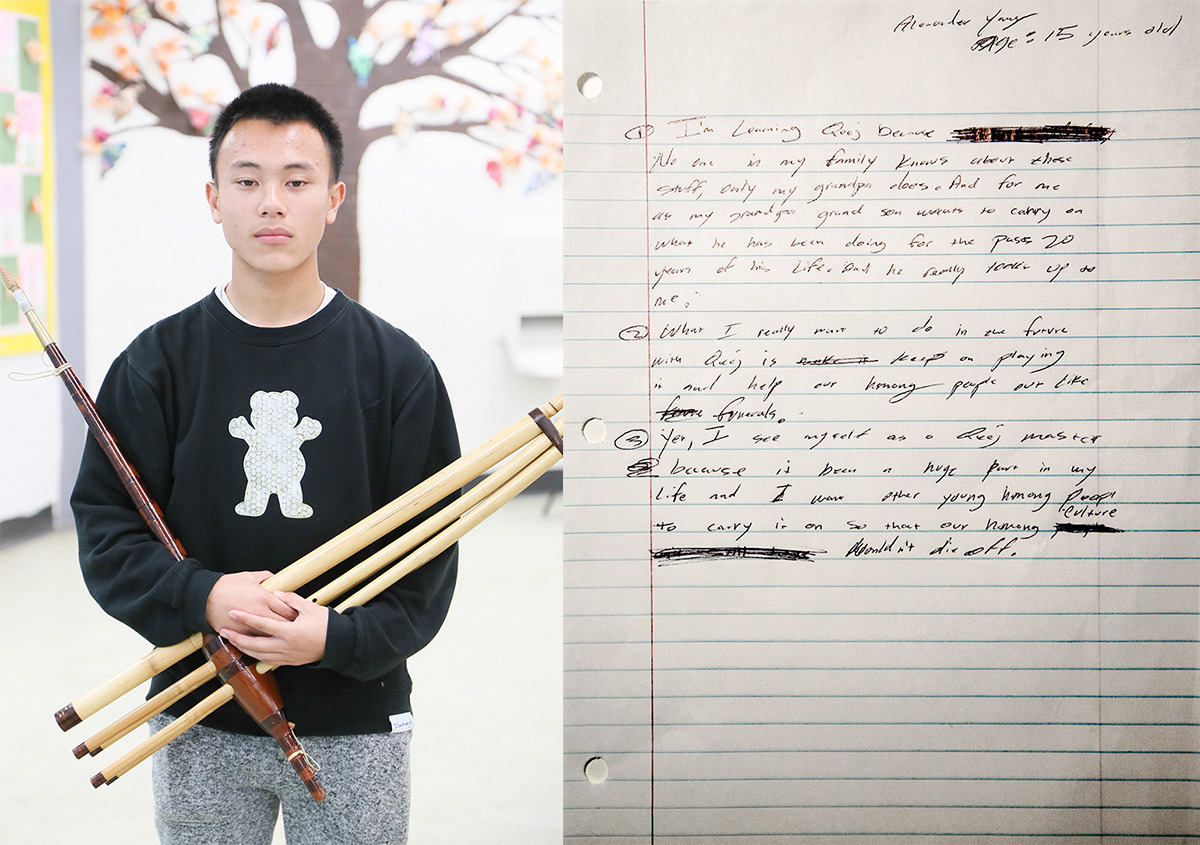

“My grandpa used to tell me there were a lot of Hmong people who would do it, but now that we’re living here … there’s not that many who know how,” says Alexander Yang, 15. Yang has been studying with Teng for two years.

Like the others, he first became aware of the qeej at a funeral, where he saw his grandfather play. He now says the instrument has become “an important part of my life.”

‘You blow, you sit, and you bite down’

Teng moves toward Andy Yang, another of his students, to adjust the mic attached to his pipes. Yang turned 21 last November and is performing his fifth qeej tu siav (pronounced “too shia”) for the funeral of Vang Her, who at the age of six fled with his family from Laos to Thailand before coming to Fresno.

The qeej tu siav is the first and most challenging song of any funeral, one intended to send the soul back to the ancestors. It describes the life cycle from birth to death and rebirth, repeating anywhere from 18 to 30 parts six times.

An elder sets a box of soda under Andy’s qeej for support. With only short breaks for water, he will communicate this life cycle to the soul for the next nine hours.

Meanwhile, guests sit along rows of maroon chairs that fill the perimeter of the chapel. In the courtyard food is prepared over large pots. Elder ladies set out tin trays of pork soup and sprouts of bokchoy, along with cuts of beef and stacks of individually wrapped rice.

From inside, Andy’s melody grows louder. Over the course of the day, it will instruct the spirit of Vang Her, whose body is dressed in a long black robe and hemp shoes traditionally reserved for Hmong kings and queens, to dine with the community.

As the lunch hour ends, the guests slowly return to their seats. Late in the afternoon, Andy is relieved by txiv qeej Richard Vang, who begins a tune that will direct Vang Her’s spirit onto a horse for his journey to the afterlife.

“You feel like it’s coming off,” says Andy after nearly nine hours, referring to the pain in his teeth and upper body. “You blow, you sit, and you bite down.”

But Andy, who only began playing the qeej tu siav the summer before, is undeterred. “I want to teach like Teng, but it’s really hard … It depends if you have the passion to teach like Teng does.”

When asked what he would be doing if not teaching the qeej, Teng shrugs. “I would be like everybody else I think. I’d just have a job. Maybe I would have a good college education.”

He says a lot of the masters play the qeej as a side gig, most days holding down regular jobs. “I should be doing that also,” he muses, before adding, “If we all do that, the kids and the younger generation will lose everything.”

This story appeared in the July 6 online edition of The Fresno Bee.